Revisiting Ancient Women: Medusa

Medusa, Michaelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1596

The story of Medusa is widely known throughout the world. Often the star of the story, Medusa herself, is portrayed as a strong, fierce feminist figure, one who’s even violent and aggressive. By embodying these qualities, Medusa challenges oppressive stereotypes of femininity and the inextricable ties between womanhood, passivity and docility.

Sounds great, right? But in the process of Medusa’s socialization into our culture, it seems we’ve lost some critical details surrounding her myth. Some critical details, which, when excluded, present us with a false sense of “wokeness” regarding the ancient Greeks and their stories. It’s time to revisit the real story of Medusa.

The famed myth opens on two women: Medusa and Athena, with the former being a priestess of the latter. Medusa was known for her stunning appearance – she had a beautiful face, mesmerizing eyes, and locks of hair as precious as strands of gold. As such, the priestess had many suitors; both men and immortals lusted after her. However, in her devotion to Athena, Medusa had sworn herself to a life of chastity, and as such, denied any and all admirers.

One day, Poseidon, god of the sea and sworn enemy of Athena, motivated by uncontrollable desire, raped Medusa on the altar of Athena’s temple. Presumably, Athena had the power to stop the rape, but chose not to, and an explanation as to why is not included in most versions of the myth.

Athena decides to curse Medusa, not Poseidon, for the attack that occurred, replacing her hair with wild snakes. Later, Perseus, a son of Zeus, slays Medusa and reduces her to just a head – one that he carries around as a trophy and uses to kill whomever he wishes.

The takeaways of this story are ridden with sexist values. Firstly, we see Medusa and her body being used as a pawn in a game between two gods, Athena and Poseidon. We then witness a woman being blamed for a man’s crime. In addition to that, the punishment Medusa receives is one that targets only her external appearance. Her head of luscious, golden hair becomes home to dirty snakes, and as such, reinforces the notion that women’s most valuable assets are their physical features.

Lastly, Medusa’s fate is sealed as nothing but a helpless head, one that a man carries around as a distorted object of pride and strength, and she’s forced into an afterlife of servitude as she quite literally executes Perseus’ personal will and agenda for the remainder of her existence. So, I’ll present a question once more: Is this really a feminist story we should acclaim?

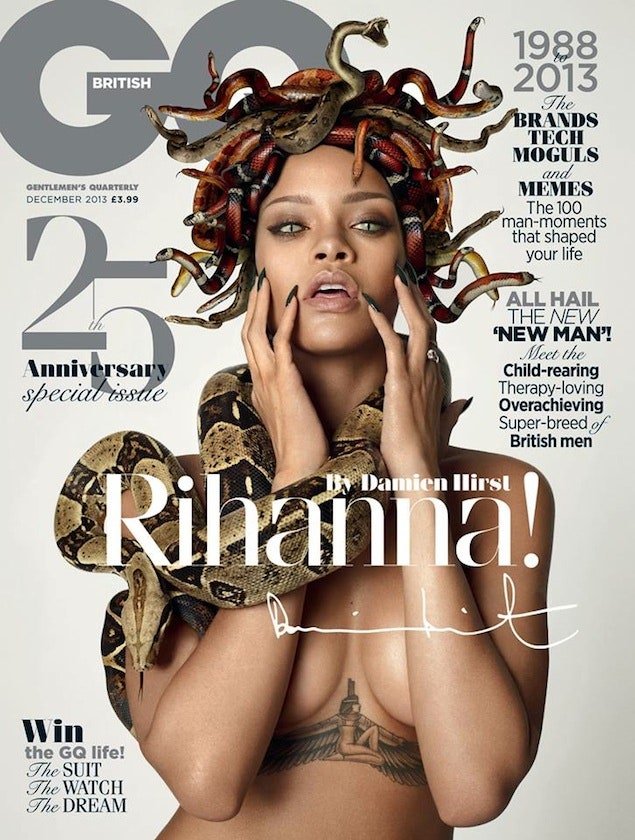

Rihanna on the cover of GQ, 2013

It is far more enjoyable to interpret the tale of Medusa through a presentist lens. It is more preferable to think of Medusa as a triumphant feminist. But I do warn that in using an alternate, 21st century viewpoint to mask specifics of this original tale, we risk expunging key details in ancient history.

If we choose to forget the underpinning themes of misogyny throughout versions of myth, we choose to forget that tropes of women’s subordination and objectification were created many millennia ago. If we make this story more palatable for our society, we lose the origins of oppressive gender roles, the same ones that we fight to dismantle to this day.

Medusa as the logo for Versace

Medusa has been co-opted as a face of female empowerment because she is one of the only female figures in Greek mythology with vengeful power. But we often forget how she gained that power in the first place – not through agency. And she doesn’t utilize it through agency either – a dynamic ironically now being played out in the 21st century as brands, media companies and cultural tropes continue to perpetuate the “myth” of Medusa, as a woman that is anything other than a victim.